This past Saturday was the 119th anniversary of the birth of Katherine Sergeant Angell White, one of The New Yorker‘s first editors. She began working for the magazine in 1925 and nurtured the talents of many of its best known writers. “She had a fabulous correspondence with them. She mothered them. She was interested in their family life, their sorrows and their horrors,” E.B. White noted in a 1980 New York Times profile. Katherine White is credited with establishing and shaping what we know of as the “New Yorker story”; discovering writers like Thurber, Cheever, Updike, and Nabokov. Katherine White, then Katherine Angell, recommended Harold Ross hire E.B., who went on to become one of the magazine’s greatest assets.

At the time her marriage to Ernest Angell was falling apart – he had come back from the First World War a very different man and had taken a mistress; Katherine found herself spending more and more time with E.B. (who everyone called Andy, a nickname he picked up at Cornell.) In 1929 Ernest became physically violent with her during an argument — she immediately moved to Reno to get a divorce. When she came back to New York her courtship with Andy progressed. They were married later that year and back at their desks the next day, postponing their honeymoon for several months.

Katherine S. White had a profound effect on the character and style of The New Yorker. Harold Ross counted on her for a great many things; in one letter he admits to Andy “for years, I have tried to defer in matters of taste to others, principally to a lady you know well, a fellow stockholder.”* Even after the Whites moved to Maine she was still an active part of the magazine – Ross sent her letters asking her to, among other things, buy a few magazines each month, keep abreast of the competition, and tip him off to any talented new writers he might need to know about.

“If it gets down to a question here of having somebody buy the magazines and send them up to you there’s a chance of incompetent judgement in the selection of the magazines. It takes an old-timer around here to do it and a person of comparatively great judgement. My only idea of euchring you into doing this job is that you qualify in both respects.”

– Letter from Harold Ross to Katherine S. White, dated April 10, 1942

Her son, Roger Angell, who wrote reviews of children’s books with his mother and who would go on to become the fiction editor of The New Yorker for several years, described her and Andy’s work habits:

In soft tweeds and a pale sweater, [she] sits at her cherrywood desk, one leg tucked under her, with a lighted Benson and Hedges in one hand and a soft brown pencil in another as she works her way down a page of Caslon-type galleys, with her tortoiseshell glasses down her nose. Her desk is littered with papers and ashes and eraser rubbings.

Across the hall Andy sits up at his pine desk, facing her…. there are messages to himself taped up on the bookcase behind…. Andy reads a passage aloud from today’s letter from Frank Sullivan or his brother Stanley or a grain merchant in Ellsworth, and my mother laughs, scarcely lifting her eyes from the page. Soon the noises of her typing out another letter to Harold Ross or Gus Lobrano are joined by the slow clatter of his Underwood: a New England light industry is again in full gear, pouring out its high-market daily product.

Last weekend I read a memoir written by Isabel Russell about the years she spent working for The Whites in Maine. The picture Russell paints of Katherine is often tainted by noxious editorial interjections – speaking of E.B. she claims

“He lived day to day in the later years with the pathetic, stout, quick-tempered, bemused invalid but he never really saw her that way. His kind heart eternally called forth the small, slender, serious bride of his youth.”

This quotation was easy to find in my copy since I was immediately moved to write “Bullshit” across the top of it when I read it. The idea that the reality of living with a woman with serious health problems (Katherine had subcorneal pustular dermatosis, a rare form of dermatitis which her doctors treated with heavy doses of cortisone) could only be mitigated by retreating into a fantasy of the past simultaneously turns Katherine into a burden, a person completely defined by her illness, and canonizes her husband for being able to tolerate her.

This is a pattern throughout the book – Katherine is painted as a demanding, disruptive force in the household and her husband is treated as if his every action, word, and thought are manna directly from the heavens. There are, however, moments when Russell steps back and allows the reader to catch a glimpse of the day to day life of the household. Here she describes Katherine’s intense concentration while reading one of her husband’s pieces:

“[K’s] eyes were glued to the typed pages he had given her; when she was engaged by any piece of printed matter, her concentration was absolute. She was so oblivious to anything around her, including entrances and exits, that it was disconcerting. If you had departed, she might instigate an exchange of ideas as though you were still there beside her. If you entered the room unsummoned, she failed to see you, and if you didn’t interrupt her, it could mean an agonizing wait. From my office, after a time lapse, I could hear her begin to discuss the piece aloud; it was several minutes before she realized the room was empty.”

– Isabel Russell, Katherine and E.B. White: An Affectionate Memoir, pg. 135

In 1958, White began to write a gardening column for The New Yorker, “Onward and Upward in the Garden” and started a correspondence with Elizabeth Lawrence. White was a passionate amateur, Lawrence was an established garden writer; the two women wrote each other letters until White’s death in 1977, at which point Lawrence began corresponding with her widower. These letters have been collected in Two Gardeners: A Friendship in Letters, a book I’ve been reading in little snatches over the past two weeks. I’ve enjoyed it, even though the subject of gardening tends leaves me a little cold. The two women discuss their gardens, their health, the weather, aging, copyright law, and the magazine business; Katherine emerges as a kind, warm, caring person, always so appreciative of all the aid and guidance Elizabeth had given her in her gardening. In return she counseled Elizabeth on publishing, provided her with bloom times from her garden, and mentioned her in her New Yorker column. In a letter written in December of 1959, Katherine apologizes for sending Elizabeth a copy of Ornamental Annuals by Jane Wells Loudon, a 19th century gardener whose books the two ladies adored:

“I send you for Christmas, with my love and deep gratitude, this battered volume. I do it with some hesitation, lest it trouble you and make you think we are on Christmas present terms and that you should send me something. I should be very cross if you did, for this is not my intention at all, and this is a one time thing that I just happen to send at Christmas time….You see, it was you, really, who first introduced me to the pleasures of Mrs. Loudon and it was you more than anyone who gave me courage to go on writing the “Onward and Upward” garden pieces, and it was you whom I’ve been pestering for two years with questions when I, a total stranger, had no right to take your time. So this is just a token of my gratitude…Please don’t be mad at me.”

In an interview with The Paris Review, White underscored how important Katherine had been to the magazine they both gave so many years of their lives to:

“I have never seen an adequate account of Katharine’s role with The New Yorker. Then Mrs. Ernest Angell, she was one of the first editors to be hired, and I can’t imagine what would have happened to the magazine if she hadn’t turned up. Ross, though something of a genius, had serious gaps. In Katharine, he found someone who filled them in. No two people were ever more different than Mr. Ross and Mrs. Angell; what he lacked, she had; what she lacked, he had. She complemented him in a way that, in retrospect, seems to me to have been indispensable to the survival of the magazine…. I had a bird’s-eye view of all this because, in the midst of it, I became her husband. During the day, I saw her in operation at the office. At the end of the day, I watched her bring the whole mess home with her in a cheap and bulging portfolio. The light burned late, our bed was lumpy with page proofs, and our home was alive with laughter and the pervasive spirit of her dedication and her industry.”

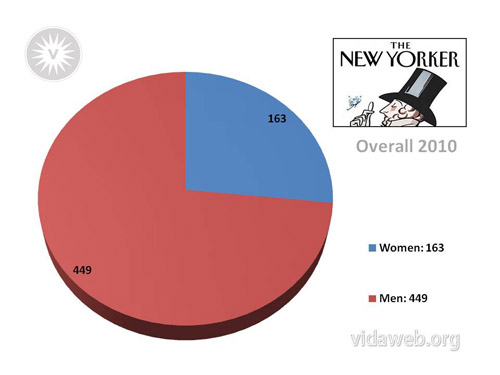

As a sad postscript, Flavia provided me with a link to a story from Vida, about the gender disparities at several modern literary magazines. Here are the 2010 figures for The New Yorker:

In light of the fact that Katharine White spent her life making The New Yorker great, seeing women still so underrepresented at the magazine is pretty goddamned sad.

In light of the fact that Katharine White spent her life making The New Yorker great, seeing women still so underrepresented at the magazine is pretty goddamned sad.

* Letter from Harold Ross to E.B. White, dated May 7, 1935

4 Comments

I have been in love with Katherine White’s work since I found “Upward and Onward in the Garden” year ago. She’s really one of the great American prose stylists, and worth reading even if you’ve good no talent for gardening (like me).

Thanks for this post.

During my last year of undergrad, I spent an entire semester studying the “New Yorker style,” including reading an entire effin’ book by John McPhee (I now know more about oranges than I ever wanted to). I’m saddened but unsurprised that Katherine White was never mentioned.

You can be a dude up in my feminism any old time with posts like this. Just lovely.

Yeah, but remember who the editor was (of the New Yorker) a few years back. Still, I bet the breakdown of staff gender wasn’t much different. Would Tina Brown qualify as a feminist?